AI thinks, humans click

AI solved the hard part and failed at the easy one

A few weeks ago, I helped a medical-device company use AI to review scientific literature from PubMed.

This wasn’t a small task. Hundreds of papers needed to be analyzed to identify only those that reported performance, safety, and adverse effects. Anyone who has done this kind of work knows what it usually means: days or weeks of careful reading by highly trained professionals.

With AI, it took minutes.

The system could read abstracts and full papers, understand medical context, discard irrelevant studies, and extract exactly what mattered. From a cognitive point of view, the problem was solved. The hardest part — understanding the science — was no longer the bottleneck.

And yet, the hardest obstacle had nothing to do with AI or medical science.

Not because the AI made mistakes. Not because the model hallucinated. Not because the logic was wrong.

It failed because the AI couldn’t download the PDFs.

CAPTCHAs, anti-bot protections, endless “are you human?” checks — mechanisms designed to stop abuse, now standing directly in the way of legitimate work.

The AI could evaluate hundreds of medical studies faster than any human team ever could — but it couldn’t click a checkbox.

Anti-bot software made sense. Once.

Anti-bot systems exist for good reasons. They were designed to protect websites from abuse, prevent mass scraping, stop fraud, and preserve business models based on ads or limited access.

For a long time, they worked under a simple assumption: automation is suspicious, humans are legitimate.

That assumption made sense in a world where bots mostly stole content, overloaded servers, or gamed systems.

But that world is gone.

The web changed how we work — quietly, completely

Over the last two decades, we moved almost all professional software into the browser.

What used to be local or client-server applications became web-based tools, running on centralized servers. CRM systems, ERPs, accounting software, HR platforms, marketing tools — everything moved to SaaS.

This shift enabled incredible innovation. Updates became instant. Collaboration became global. Software became cheaper to distribute and easier to improve.

The browser became the universal interface for work.

And nobody questioned it.

AI doesn’t need a browser

AI breaks that assumption.

AI doesn’t need buttons, dropdowns, or PDFs. It doesn’t benefit from dashboards or pagination. It doesn’t care about layouts or modal windows.

AI needs access to information and permission to act.

And yet, we force it to operate through interfaces designed for humans — fragile, visual, and constantly changing.

To make this work, we invented an entire ecosystem of tools.

The promise — and pain — of web automation

Browser automation, web scraping, RPA, headless browsers, workflow bots — an entire ecosystem has emerged promising the same thing: let AI do the work for you.

In reality, these approaches are far more fragile than they appear. They rely on user interfaces that were never meant to be stable integration points, and they break in ways that are both frequent and unpredictable.

A button moves. A label changes. A CAPTCHA appears. A login flow is updated. None of these changes are announced, and none of them are considered breaking changes by the software vendor.

Yet each one can silently bring automation to a halt.

You’re always one minor UI redesign away from a production outage. Automation that depends on software pretending to be human is, by definition, unstable.

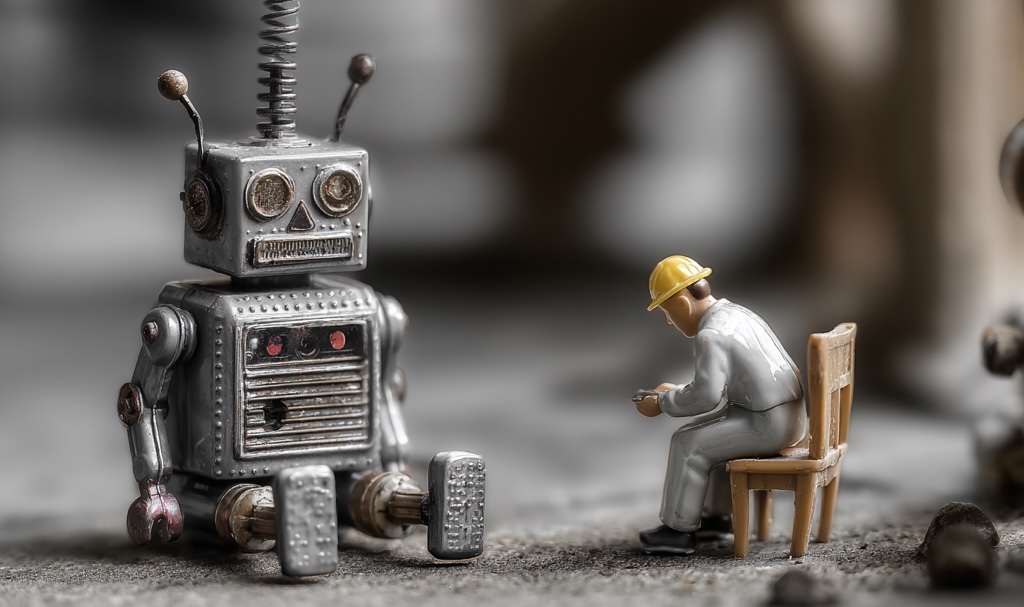

The world, completely upside down

This is where things become absurd.

Today, AI handles the most intellectually demanding parts of many workflows. It reads, reasons, compares, summarizes, and decides.

Meanwhile, humans are forced to do the most mechanical tasks imaginable: downloading PDFs, clicking “I am not a robot,” solving image puzzles, retrying failed uploads.

Humans are reduced to manual adapters between web UIs and AI systems.

We didn’t automate work. We rearranged the pain.

A thriving business built on friction

Unsurprisingly, there are companies that specialize in this exact problem.

Services like 2Captcha, Anti-Captcha, DeathByCaptcha, and similar platforms exist to solve CAPTCHAs by routing them to real humans, somewhere in the world, who click the boxes and solve the puzzles.

In other words, we turned human labor into an API so that automation can continue.

More AI leads to more automation attempts. More automation leads to more anti-bot measures. More anti-bot measures lead to more manual work.

This feedback loop is impressive — and deeply broken.

“Anti-scraping” without anti-thinking

Some companies don’t even rely on technical barriers. They rely on contracts.

Many websites include “anti-scraping” clauses in their terms of service. But what does scraping even mean when an AI automates a task that a human is explicitly allowed to do?

If I can legally read a document, download a PDF, and analyze it, why does it become questionable when software does the exact same thing on my behalf?

The answer is often vague. Conveniently so.

We’re asking the wrong question

The real problem is not abuse. Abuse can be handled with rate limits, authentication, and accountability.

The real problem is that applications still ask the wrong question.

Instead of asking: “Are you human?”

They should be asking: “Are you a legitimate user or a legitimate automation?”

These are very different things.

If access is free via a browser, it should be accessible via an API. If workflows are allowed for humans, they should be allowed for authenticated automation. CAPTCHAs are a crude tool for a much more nuanced world.

Yes, ads complicate the picture. Yes, business models matter. But forcing highly paid professionals to spend time clicking through filters so AI can do its job is not sustainable.

Enterprise software must evolve — fast

As AI continues to take over more cognitive work, enterprise software faces a choice.

It can remain UI-centric and force humans to babysit automation.

Or it can become AI-native and expose workflows, data, and permissions in a way that machines can use responsibly.

The companies that win won’t be the ones with the nicest dashboards.

They’ll be the ones that stop asking machines to pretend they’re human.

Final thought

Anti-bot systems were originally built to stop machines from pretending to be people.

Somewhere along the way, we inverted that logic. Today, we increasingly pay people to perform mechanical tasks so that machines can do the thinking.

That inversion should make us pause.

It’s probably not the future of work — but it is a clear warning sign that our software architectures haven’t caught up with the world we’re now living in.